It takes a village

In the intricate landscape of modern health care, the relationship between doctors and pharmacists stands as a crucial yet often understated dynamic. While both professions share the common goal of patient well-being, cooperation between them can sometimes feel like it’s just too complicated.

Last year, we delved into the potential synergies between pharmacists and physicians, highlighting the challenges posed by “scope creep.”

This year, our focus shifts to shedding light on these challenges, the evolving landscape of healthcare legislation, and exploring avenues for fostering greater collaboration amidst the tensions that may arise.

Pandemic ripple effects

A side effect of the COVID-19 pandemic was that pharmacies became the go-to place for patients to get their vaccines. While the American Medical Association opposed this practice on “scope expansion” or “scope creep” grounds, the fact of the matter is that it worked out pretty nicely for individuals looking to get the shot.

(And not for nothing, but drugstore businesses also benefited from having new customers walk all the way to the back of stores to get to the pharmacists and often left the store with other merchandise besides merely the vaccine).

Leaving vaccines to pharmacists also allowed physicians to focus on the important task of disease treatment instead of getting bogged down with all that prevention of otherwise healthy patients.

Yet trade groups representing pharmacists and physicians are at loggerheads over this job-sharing approach. Emblematic of this conflict is a bill introduced last year in Congress, H.R. 1770, the Equitable Community Access to Pharmacist Services Act. This proposed legislation would continue to allow pharmacists to both test and provide vaccinations for COVID-19, as well as flu, strep throat and respiratory syncytial virus. The bill enjoys 121 bipartisan co-sponsors and the support of 190 outside groups and is currently in committee. It is seen as being especially helpful in rural and underserved areas. Importantly, it would provide pharmacists with payments from Medicare patients.

[Read more: Stepping up: Supermarket pharmacy report]

The American Pharmacists Association applauded the proposed legislation when it was released in 2023. “H.R. 1770,” said Paul W. Abramowitz, CEO at the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, and Ilisa Bernstein, then-interim CEO at APhA, “would empower older Americans, who are at higher risk of contracting infectious diseases and needing hospitalization, to continue to rely on services provided by pharmacist in their local communities.”

Meanwhile, the AMA opposes the legislation, taking the view that pharmacists are unqualified to diagnose and treat patients and thus increases the chances of patient harm. “Pharmacists do not have the education and training necessary to assume the role of a physician,” AMA executive vice president and CEO James L. Madara, M.D., wrote in a letter to the Congressional authors. “This fact in isolation raises serious concerns about the underlying merits of this legislation.”

Yet in the real world, there is more cooperation than conflict. Pharmacists know more about medications than any other healthcare professional. This makes them valuable in the chain of care for a system predicated on pharmaceuticals.

10 ways pharmacists help physicians

- Optimize drug therapy—escalate therapy or identify medications that are expired, duplicates, or are no longer needed.

- Replace drugs with safer or less costly alternatives.

- Help patients taking multiple medications, especially when prescribed by multiple doctors, by suggesting new drugs that might manage multiple conditions simultaneously so patients can decrease the number of drugs taken and hopefully cut down on side effects.

- Identify drug-drug interactions.

- Inform physicians about medications that now exist as generics.

- Improve compliance by helping patients who are not adhering to the protocol.

- Identify patients who are no longer capable of managing medication protocols.

- Provide vaccinations.

- Test and manage diabetes patients, especially those who are failing to manage their treatment plan.

- Test and manage hypertension patients.

“Unfortunately, there is a disconnect between the collaborative, team-based care that happens every day in the real world versus lobbying in Washington that aims to restrict the role of pharmacists and reimbursement for their services,” said Tom Kraus, vice president of government relations for ASHP, the association of pharmacy professionals representing 60,000 pharmacists in all patient care settings. “Despite some negative lobbying, pharmacists are fully trained and qualified to provide the type of care in this legislation.”

Can’t we all get along?

Drugstores and pharmacists benefitted from expanded patient access during the vaccination rush from COVID-19, but that was in the once-in-a-century global pandemic. The squabble is clearly continuing with trade groups representing the two sides opposing each other on the H.R. 1770 Congressional legislation. But that’s not the only issue at play.

So is there anything to be done with these two groups, which are pillars of the American allopathic healthcare system? Actually, yes.

At the heart of the discourse, however, lies a fundamental conflict: opposing viewpoints on the scope of practice. On one side of the spectrum are voices like Hae Mi Choe, Pharm.D., the chief population health officer at the University of Michigan Health, who advocates for the integration of pharmacists into physician practices, citing tangible benefits in improving quality of care and reducing costs.

In one published study, Choe’s group noted the value of pharmacist integration in helping with issues such as inappropriate drug use, increasing complexity of drug regimens and continued pressure to control costs. Pharmacists provide comprehensive medication review services and deliver disease management around diabetes, hypertension and hyperlipidemia.

Choe and her team, in conjunction with the AMA, has produced a STEPS Forward toolkit to help physicians learn how to integrate a clinical pharmacist into their practices.

But integrating clinical pharmacists into doctors’ offices is one thing. It’s quite another to figure out how community pharmacists working in the backs of drugstores can help physicians working in their separate offices improve patient care.

“Is it possible? Yes. Is it easy? Probably not,” said Choe. “You need to establish an intentional partnership where both parties make decisions around workflow ahead of time in order for it to work.”

[Read more: Serious threats, big opportunities]

On the other end of the spectrum is former pharmacist David Foreman, Pharm.D., who quit the business out of frustration with the system.

“One of the reasons I left pharmacy is that the drug and insurance industries took the fun out of being a pharmacist,” he said. “We made very little impact on what was prescribed and patient care. Even the prices were set, which meant they even took the entrepreneur out of it for me.”

In the middle is Erik Goldman, owner and editor of Holistic Primary Care—News for Health & Healing, which reports to practitioners of a certain philosophical bent on the politics, economics and science of healthcare. He sees a huge benefit for pharmacists who both maintain strong lines of communication with doctors in the community as well as have knowledge about nutrition and herbs to help the healing process for all those patients who routinely use dietary supplements.

“But how many pharmacists like that do we have in this country?” said Goldman. “Probably not too many.”

To add insult to injury for patients, Goldman noted that both doctors and pharmacists work “in the insurance-driven medical matrix,” which will not compensate them for their consultation time, and which rewards the fast fulfillment of physician prescription requests. “So it seems to me that pharmacists face the same set of incentives and disincentives as doctors,” said Goldman.

Pharmacist integration practices

Last year, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services extended the governing legislation allowing pharmacists to deliver COVID-19-related testing, vaccines and treatment through the end of 2024.

Allowing pharmacists to diagnose patients based on test results is opposed by the AMA but is seen as making a whole lot of common sense when it comes to diagnosing flu, strep throat or a UTI. Managing hypertension and diabetes have become the top two pharmacist-led roles, which should also include a review of polypharmacy issues and medication tapering (including opiates). Pharmacists might also answer patient calls or emails about medication-related questions.

That all sounds great in theory, but challenges abound, from groups like the AMA that oppose efforts to democratize healthcare away from highly trained physicians; from individual practitioners who just don’t have the bandwidth to think about enlisting others in healthcare decisions that come in 15-minute increments with patients and from the balkanized healthcare system with different specialists dispensing different medications and nobody really able to synthesize all these treatments for the patient.

Nobody, that is, except for pharmacists. Even then, it’s a bit of a tall order.

“Community pharmacists may have the medication list because patients get all their drugs from the pharmacy, but they don’t have access to medical records and don’t have access to what physicians are thinking,” explained Choe, who pioneered the U of M program to integrate pharmacists into medical practices. “So there’s a mismatch. Nobody has all the data, per se.” Michigan is not the only state stepping into the vacuum from the absence of federal legislation. The low-hanging fruit is usually around medication therapy management —that comprehensive approach to optimizing medication use around drug interactions, duplications from different practitioners’ prescriptions, inappropriate dosages, adherence strategies and side effects.

MTM services are of particular value for the one in five polypharmacy adults between the ages of 40 and 79 taking five or more different drugs for chronic conditions.

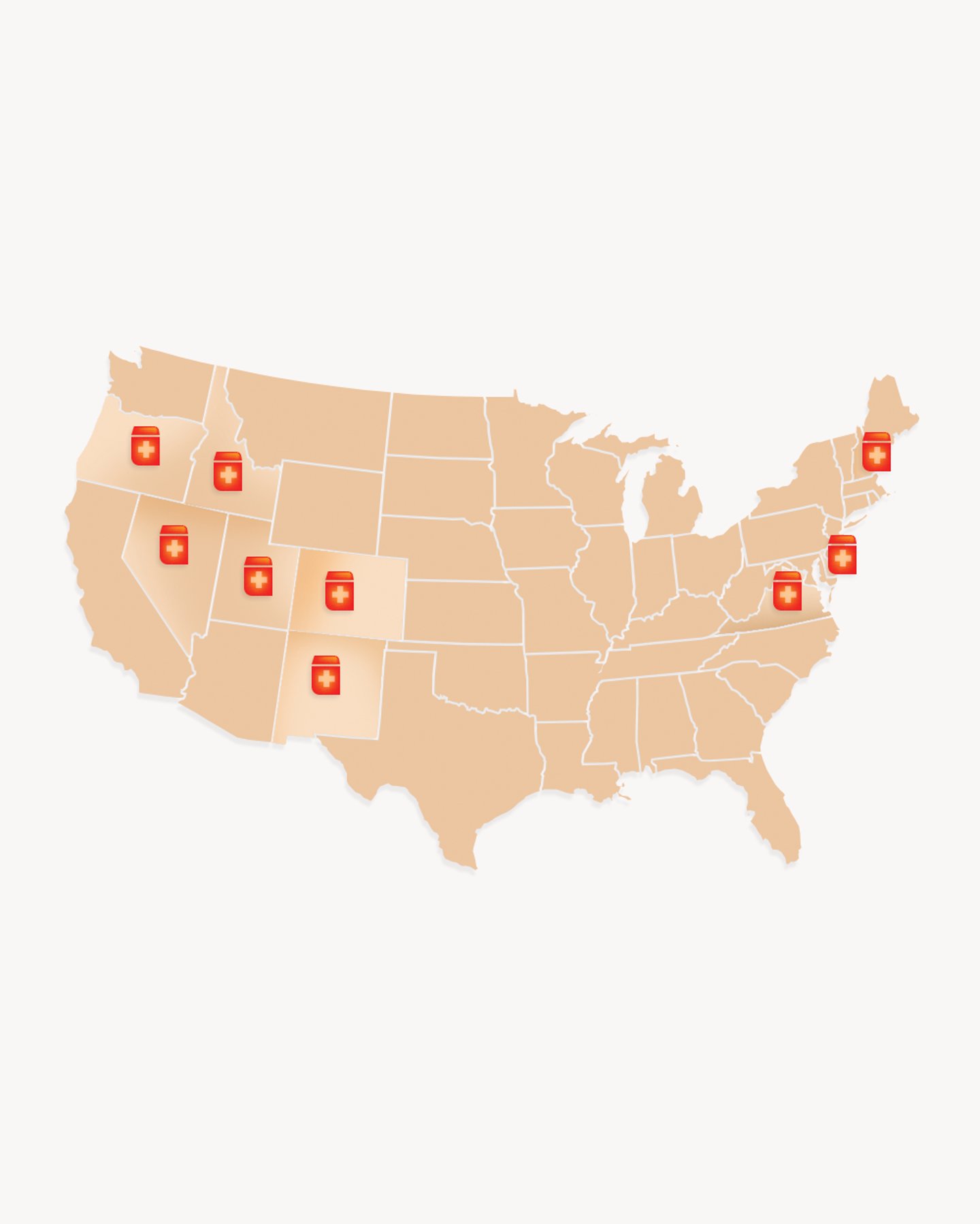

States with MTM regimes include California, Colorado, Minnesota, New York, North Carolina, Texas and Washington. Each state runs MTM services differently depending on various factors such as provider collaboration models, reimbursement mechanisms and the healthcare infrastructure unique to each state.

“Patients who are eligible to receive services are not all getting that,” said Choe. “Even if they know they have this benefit, who’s going to deliver these services, right?”

Choe pointed to a typical challenging example of patients receiving medications from several different doctors and they don’t always work together to resolve medication-related problems.

“Pharmacists who have appropriate training and appropriate knowledge would be the best person to do that,” said Choe. “But if they’re in a busy community pharmacist setting, it’s challenging to provide a high-quality, comprehensive medication review without dedicated time and patient-specific medication information.”

[Read more: Envisioning an ideal model for retail pharmacy]

While the AMA has acknowledged the value of integrating pharmacists into medical practices, citing the success of a program in Oregon, the trade group is vehemently opposed to both H.R. 1770 but also most every attempt that expands scope of practice for pharmacists.

The ASHP continues to advocate on behalf of pharmacists, creating model legislation that allows physicians and pharmacists to team up and optimize medication use, as well as other legislation prototypes for states to take up around increasing patient access to pharmacists with medications for opioid use disorder.

The ASHP has an annual best practices award; one recent standout is a pharmacist-led remote patient monitoring concept that improves cardiovascular health outcomes.

If you’re thinking such proposals make sense for patients and save money for the system, you’re not wrong. Yet these also represent something of a shot across the bow of the physician-led system backed by the AMA.

Even relatively conflict-free approaches have headwinds. For example, the Pharmacist eCare Plan, which shares electronic health records between physicians and pharmacists, runs into the buzzsaw of EHR capabilities, reimbursement policies and adherence to relevant data standards.

“The Pharmacist eCare Plan has yet to reach its full potential,” said Kurt Proctor, Ph.D., R.Ph., senior vice president of strategic initiatives at the National Community Pharmacists Association. “Primarily because EHR vendors used by prescribers have yet to implement it in their systems to facilitate two-way communications.”